On this page

What is prevention?

Creating communities free from family violence, violence against women and gendered violence relies on a connected, resourced and well-supported system across a continuum, comprising primary prevention, early intervention, response and healing and recovery initiatives (13). Each part of this continuum must be adequately resourced and designed to effectively respond and work together to prevent violence, intervene to decrease the risk of further or escalating violence and to ultimately stop it from occurring in the first place.

In this report, ‘prevention’ is used in reference to primary prevention unless otherwise specified.

Family violence prevention continuum

In the PDF publication of this report, the family violence prevention continuum was presented as 'Figure 2'.

Primary prevention

Primary prevention focuses on stopping violence before it starts by changing the conditions that allow it to happen in the first place. It addresses the attitudes, social norms, practices, structures and power imbalances that influence individual behaviour.

It works across communities, organisations and society in setting where people live, learn, work, socialise and play to change the social conditions that produce, drive, excuse, justify or even promote gendered violence.

Preventing family violence, violence against women and all forms of gendered violence requires taking action to address multiple, intersecting drivers of violence. This includes the gendered drivers set out in Our Watch's Change the story, as well as inequality, stigma, discrimination and marginalisation experienced by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, people from migrant and refugee communities, people of colour, LGBTIQA+ communities, people with disability, older people, and children and young people.

Examples:

- Whole-of-institution strategies and organisational policies to prevent and address sexual harassment

- Programs that promote equality and respect in settings such as sport and recreation clubs, workplaces and higher education

- Legislative reform (e.g. positive duty and the Gender Equality Act 2020 (Vic))

- Respectful Relationships in schools and early childhood education

- Consent education campaigns

Early intervention

Early intervention (sometimes called 'secondary prevention') involves working with people at higher-than-average risk of using or experiencing violence to prevent it starting, escalating or recurring. It focuses on helping people, families, communities and organisations identify and respond to early signs of or risk factors for violence.

People or communities might be considered at risk if they have attitudes that support or excuse family or gendered violence, or agree with rigid or harmful ideas, or have used or experienced (including witnessed) violence previously.

Primary prevention and early intervention work together by unwinding the harmful attitudes held by people who have a potential to use violence, by supporting them to learn new behaviours, take responsibility for their choices, and implement healthier ways of being and relating to others.

Examples:

- Programs to support at-risk young men and boys

- Therapeutic child and adolescent programs

- Health justice partnerships that enable early identification and referral to support people who have experienced violence

- Housing programs that support people at risk of family violence

- Victoria's Family Violence Multi-Agency Risk Assessment and Management Framework (MARAM) is a key system enabler, ensuring services and practitioners across a range of sectors have a shared understanding of family violence and effectively identify, assess and manage family violence risk with the aim to increase the safety and wellbeing of Victorians.

Response

Response (sometimes called 'tertiary prevention') refers to services for people who have experienced or used violence. It aims to intervene, including provision of immediate safety, coordinated support, case management, health services, justice responses, and accountability for people using violence.

Primary prevention and early intervention frameworks underpin response by providing a structural analysis of family and sexual violence.

When violence is prevented from happening in the first place or happening again, it lessens the load on the system responding to violence and supports our community to live violence-free futures.

Examples:

- Crisis and emergency housing

- Specialist family and sexual violence services

- Men's behaviour change programs

- Legal services

- Victims of crime support

- Police, child protection and criminal justice services

- Intervention orders and legal advice on family law, child protection and other matters

- Medical treatment and forensic assessments

Healing and recovery

Healing and recovery is about supporting people to find a sense of safety, health and wellbeing following the trauma of violence. Recovery can be a long process and can be particularly difficult when the person who used (or is using) violence is still in someone's life. It is supported through long-term services that focus on psychological and physical healing, integrating and managing the deep impacts of trauma.

Primary prevention reinforces this by offering an analysis of power and control, explaining that people who have experienced violence are not responsible for the abuse that occurred to them, or for the choice of the person who used violence.

Examples:

- Trauma-focused counselling

- Therapeutic support groups

- Peer support

- Lived experience advocacy

- Culturally safe camps and yarning or healing circles

- Housing security

- Social support

- Restorative justice

An overview of Aboriginal-led and self-determined prevention

Aboriginal self-determination is fundamental to effective and just family violence prevention. Self-determination recognises the rights of Aboriginal communities to lead, design, be resourced for, and deliver responses grounded in cultural knowledge, priorities and strengths (16-18).

ACCOs and community leaders have been pioneers of violence prevention work in Australia. Aboriginal-led family violence prevention efforts in Victoria typically differ from whole-of-population (or ‘mainstream’) approaches in three ways:

- they focus on the ongoing impacts of colonisation as a key driver of family violence

- they are often delivered as part of a holistic approach to wellbeing

- they often form part of an integrated approach to family violence primary prevention, early intervention, response and recovery.

Aboriginal-led prevention programs work with people within the context of their families, communities, Country and culture, recognising that all play an important role in wellbeing and safety across interconnected physical, social, emotional, cultural and spiritual dimensions (19). They focus on strengthening and supporting connection to culture and identity as protective factors for preventing, identifying, escaping and healing from violence. Aboriginal prevention efforts also include programs and partnerships that seek to promote cultural safety in the service system, recognising that access to community services where people are treated with respect and without racial prejudice are foundational to Aboriginal self-determination and supporting strong families and strong communities.

Dhelk Dja Regional Action Groups continuously highlight the importance and efficacy of community-led programs and initiatives with respect to addressing family violence within Aboriginal communities. Such approaches are placed-based and centre on prevention, moving beyond crisis response, recognising the importance of culturally grounded, person-centred support for those affected by violence, those using violence and broader family and community impacted by violence.

Aboriginal Gathering Places are also central to the prevention of family violence. These important community hubs provide culturally safe spaces for community to connect, share knowledge, belong and celebrate their culture. Aboriginal Gathering Places offer a range of services, programs and cultural activities, such as children’s camps, men’s behaviour change on Country and women’s groups. They also serve as educational resources for the broader community. Gathering Places located in regional settings hold a significant role in community, as there may not be many other services available for community in such areas.

Aboriginal people – particularly women and children – face disproportionately high rates of violence; however, it is important to recognise that this is a whole-of-community problem and not specific to Aboriginal communities and families. Family violence is not a part of Aboriginal culture, and the high rates of violence impacting on Aboriginal communities today can be traced back to the impacts of colonisation and ongoing systemic racism. Notably, Aboriginal women and children experience violence at the hands of people (predominantly men) from all different cultural backgrounds, and in many parts of Victoria, the vast majority of Aboriginal women have non-Aboriginal partners (16). Mainstream or ‘whole of population’ prevention agencies have an important role to play in addressing the intersecting drivers of violence against Aboriginal women, children and families – particularly addressing the legacy of colonisation and racist misogyny among non-Aboriginal people. However, it is crucial that Aboriginal communities and ACCOs lead the way, ensuring efforts to prevent family and gendered violence against Aboriginal peoples are holistic, culturally safe, centred on healing and rooted in Aboriginal self-determination.

To do this work, Aboriginal-led organisations need to be resourced at the scale required, and over the long term. Inadequate and lapsing funding for ACCOs and Aboriginal community-led prevention work compromises effective implementation and meaningful outcomes, creating vulnerability for successful programs, staff, community trust and momentum for change (19).

Recognising Aboriginal leadership and the importance of self-determination in family violence prevention align closely with Victoria’s pathway to truth-telling and Treaty, including the work of the Yoorrook Justice Commission, the First Peoples’ Assembly of Victoria and the Dhelk Dja Partnership Forum.

Yoorrook’s hearings have highlighted the enduring impacts of colonisation including dispossession, child removal, racism and intergenerational trauma, and the link between these injustices and family violence. The Dhelk Dja Partnership Forum brings together Aboriginal people and organisations leading family violence work in their communities across the state with Victorian Government representatives (20). As a core part of this forum, the Dhelk Dja Koori Caucus elevates community voice, pays respect to lived experience, advocates for systemic change and ensures stronger government accountability across the family violence system – from prevention to early intervention, crisis response and healing (21).

The Dhelk Dja Family Violence Prevention Framework is currently in development to refresh the existing Indigenous Family Violence Primary Prevention Framework. The refresh will establish an overarching framework for promoting, celebrating and guiding community-led efforts to prevent family violence against Aboriginal people. It will also offer guidance on effective and sustainable community-led prevention activities that promote the safety, wellbeing and healing of Aboriginal people and communities in Victoria. This will be key to supporting ongoing investment, leading practice, and monitoring, evaluation and learning of shared outcomes for preventing family violence and violence against Aboriginal people, in support of the vision for a future where all Aboriginal people are culturally strong, safe and self-determining, with families and communities living free from violence.

The broader prevention sector has an obligation to learn from and support Aboriginal-led and self-determined prevention, to be ready for upcoming Treaty in Victoria.

How can violence be prevented?

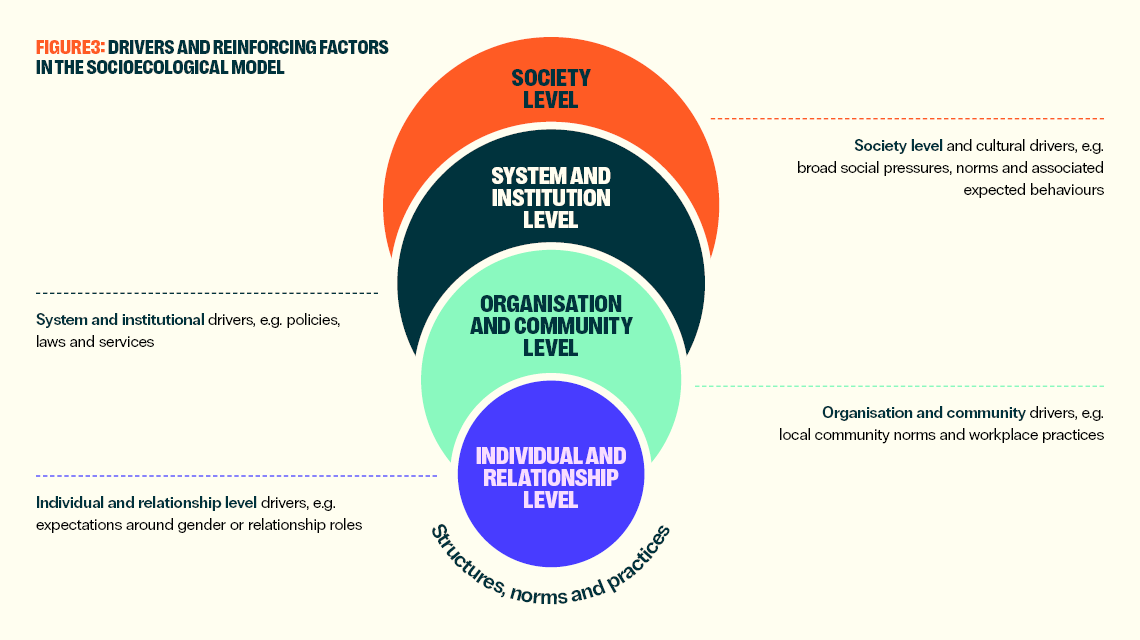

Violence against women and family violence – like any health or social issue – is driven by factors at each level of the social ecology (4, 16, 22).

Our Watch conducted a rigorous review and identified four gendered drivers of violence against women at a population level:

- condoning of violence against women

- men’s control of decision making and limits to women’s independence in public and private life

- rigid gender stereotyping and dominant forms of masculinity

- male peer relations and cultures of masculinity that emphasise aggression, dominance and control (4).

Beyond the gendered drivers, there are other important factors that can affect violence, increasing the risk, likelihood, frequency and severity. These include:

- condoning of violence in general that frames men’s violence as a normal part of life.

- experience of, and exposure to, violence; for example, having grown up with family violence or in a community where people regularly use other forms of violence.

- weakening of prosocial behaviour, including events or circumstances that reduce empathy, respect, and concern for women (e.g. heavy alcohol consumption, climate disaster, and financial stress)

- resistance and backlash to prevention and gender equality.

In addition, there are other forms of family violence that have distinct drivers that intersect with the established gendered drivers of violence against women. Evidence shows continued effort to address the gendered drivers of men’s violence against women is likely to also help prevent particular forms of family and gendered violence, including elder abuse, child maltreatment and women’s intimate partner violence against men (23).

An intersectional approach to prevention

Prevention efforts in Victoria are largely informed by Australia’s shared national framework for the prevention of violence against women, Change the story, as well as other complementary frameworks such as:

- Changing the picture which sets out specific drivers of violence against Aboriginal women (24)

- Changing the landscape which sets out drivers and reinforcing factors of violence against women with disability (22)

- Pride in Prevention which highlights drivers of violence against LGBTIQA+ people (9).

These frameworks are crucial to an intersectional approach that recognises and addresses the shared and unique drivers violence, oppression and discrimination on the basis of gender, race, Aboriginality, disability, age, class and sexuality.

An intersectional approach doesn’t ask us to stop using a gendered lens. It asks us to see gender as always interacting and intersecting with other forms of discrimination, institutional policies and political forces (25).

Efforts to prevent violence are only effective when society, systems, organisations, communities, families and individual relationships are aligned in promoting safety, respect and equality for all.

Prevention in Victoria

Victoria has a rich history of leadership and expertise in the prevention of gendered violence, family and sexual violence and violence against women – built upon decades of feminist, human rights and public health advocacy and leadership, including by victim survivors, frontline workers, global agencies such as the United Nations and health promotion agencies such as VicHealth that supported the development of foundational frameworks to address gendered violence.

The Minister for the Prevention of Family Violence and newly created role of the Parliamentary Secretary for Men’s Behaviour Change are instrumental in unifying government primary prevention efforts.

Victoria’s prevention infrastructure is also unique as Victoria is the only state or territory to have a statutory body dedicated to the prevention of family violence and violence against women. Respect Victoria, as this dedicated expert body, works with the sector, community and government to drive state-wide primary prevention activity and outcomes. In particular, Respect Victoria holds an important partnership with Family Safety Victoria to deliver primary prevention activity and, together, keep a strong focus on primary prevention in Victoria.

A Women’s Health Services Network report showed that the Victorian rate of violence against women experienced over the previous two years has fallen from 8.1% in 2016, when it was well above the national average of 7.7%, to an estimated 5.3% in 2022, compared to a national average of 6.6% (26, 27) (footnote 1). While the only acceptable rate should be zero, we can be cautiously hopeful to see the fall in Victoria’s rates of violence against women.

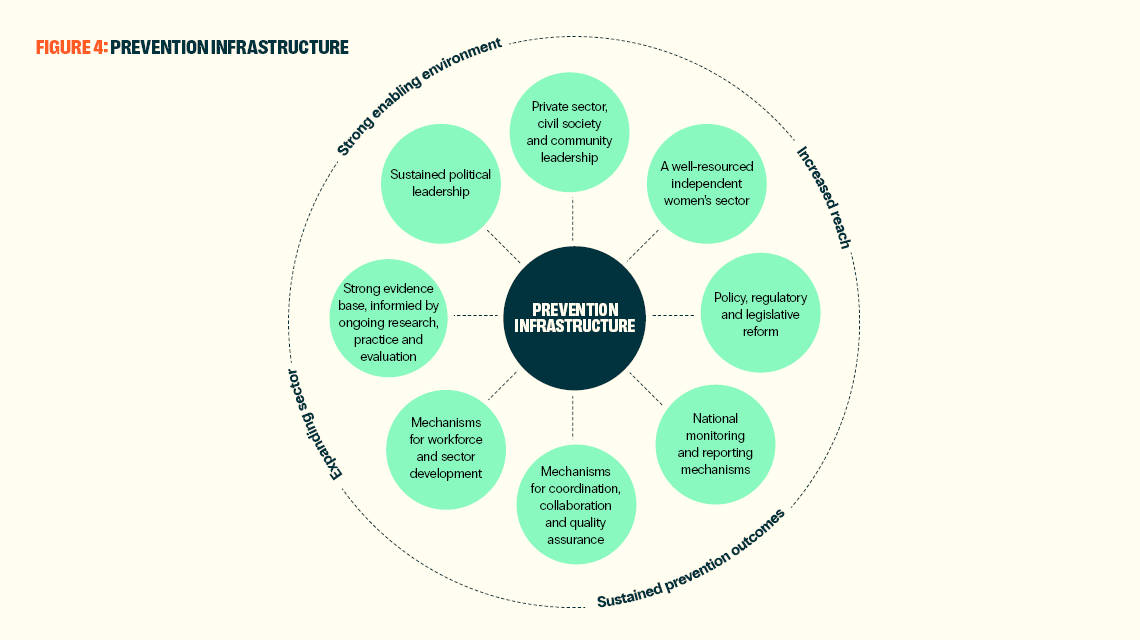

Victoria has a well-developed primary prevention infrastructure, which can best be defined as the essential foundations that enable prevention work to happen in an effective and impactful way, as outlined in Figure 4 below (28).

Prevention system infrastructure

A snapshot of key roles and responsibilities in Victoria's prevention system (footnote 2). In the PDF publication of this report, these lists were presented as 'Figure 5'.

Federal agencies, alliances and organisations with prevention responsibilities

- Domestic, Family and Sexual Violence Commission

- Workplace Gender Equality Agency

- Our Watch

- eSafety Commissioner (eSafety)

- Department of Social Services

- Australia's National Research Organisation for Women's Safety (ANROWS)

- National Women's Safety Alliance

- National women's alliances (footnote 3)

Victorian Government departments with prevention responsibilities

- Family Safety Victoria: Whole-of-government coordination and system governance, statewide prevention programs and workforce development, and the Dhelk Dja partnership with Aboriginal communities

- Department of Families, Fairness and Housing: Office for Women, child and family services, equality, housing and ageing well

- Department of Jobs, Skills, Industry and Regions: Local government portfolio, Sports and Recreation Victoria, Office for Women in Sport and Recreation

- Department of Health: Victorian Public Health and Wellbeing Plan, support for municipal planning and the Victorian Women's Health Program, Integrated Health Promotion funding

- Department of Education: Respectful Relationships

- Department of Justice and Community Safety: Legislative amendments, justice policy, alcohol and gambling policy, and crime prevention portfolio

State agencies with prevention responsibilities

- Respect Victoria: Research and monitoring and evaluation, social change and community mobilisation efforts, policy and funding advice, family violence prevention practice

- Commission for Gender Equality in the Public Sector: Oversees implementation of the Gender Equality Act

- Family Violence Reform Implementation Monitor: Oversaw whole of government accountability for family violence reform arising from the 2015 Royal Commission into Family Violence (footnote 4)

- Victorian Equal Opportunity and Human Rights Commission: Oversees compliance with key state-based human rights legislation, including the positive duty to prevent sexual harassment and discrimination on the basis of sex, gender and other protected attributes, and new prohibitions on gendered hate speech and conduct

- WorkSafe Victoria: Oversees compliance with the Occupational Health and Safety Act, including delivering campaigns, education and guidance to support workplaces to prevent gendered violence at work

Key non-government organisations or groups that provide prevention training, evidence and/or expertise

- Mainstream:

- Safe and Equal

- Women's Health Services Network

- Gender Equity Victoria

- Sexual Assault Services Victoria

- Victorian Women's Trust

- Jesuit Social Services

- Community-led or specialist

- Women with Disabilities Victoria

- Multiculturla Centre for Women's Health

- Djirra

- VACCA

- Zoe Belle Gender Collective

- Rainbow Health Australia

- Setting specific

- Municipal Association of Victoria

- Australian Women's Health Alliance

- Community Legal Centres

- Celebrate Ageing

- Seniors Rights Victoria

Local leaders of prevention activity in particular settings and communities

- Specialist family violence services and sexual assault services

- Women's Health Services and community health services

- Elder Abuse Prevention Networks

- Community organisations

- ACCOs

- Dhelk Dja Regional Action Groups

- Local governments

- TAFEs and universities

Where prevention takes place

Settings are important sites for prevention work. Essentially, they are places where people live, work, learn and socialise. Prevention work in settings, or settings-based approaches, engages large cross-sections of the community and can directly impact on social norms, organisational practices and institutional structures (4).

- Education (schools and early childhood)

- Workplaces

- Sporting clubs and institutions

- Media and advertising

- Health services

- Community and women's legal services

- Faith-based entities

- Local government

- Social, community and family support services

- Universities and TAFEs

- Digital spaces

Why preventing violence is important

The social and economic impacts of violence

Gendered violence, family violence and all forms of violence against women, children and gender diverse people are profound violations of human rights that cause widespread and preventable grief, harm and loss.

Individual impacts of gendered violence

In the PDF publication of this report, these impacts were presented as 'Figure 7'.

- 1 in 4 women in Victoria have experienced intimate partner violence from a male partner since the age of 15, and 1 in 5 have experienced sexual violence.

- 1 in 14 men in Australia have experienced intimate partner violence since the age of 15, and 1 in 16 have experienced sexual violence.

- Men are more likely to be physically assaulted by a man they don't know (1 in 5) than by a man they know (1 in 7) or a woman they know (1 in 11)

- Around 1 in 3 women and 1 in 5 men report experiencing sexual abuse during childhood

- 1 in 3 Australian adults report experiencing physical abuse during childhood

Source: (27, 29)

Disproportionate impacts of violence on people who experience overlapping and compounding forms of oppression and inequality

In the PDF publication of this report, these impacts were presented as 'Figure 8'.

- An estimated 3 in 5 First Nations women have experienced intimate partner violence

- 1 in 6 older Australians have experienced elder abuse in the last 12 months

- 2 in 3 LGBTQ Victorians have experienced family violence

- Almost half of migrant women in Australia have experienced workplace sexual harassment in the past five years

- People with disabilities are twice as likely as people without disabilities to have experienced violence since the age of 15

Beyond the immediate physical and psychological harm

People who have experienced violence often face long-term effects such as trauma, housing insecurity, disruptions to work and study, and significant financial cost (35, 36). These impacts ripple across families, communities, workplaces, and the broader economy.

In 2015–16, family violence in Victoria cost an estimated $5.3 billion, of which $2.6 billion was borne by victim-survivors and their families, $1.8 billion by the State Government and $918 million by the community and broader economy (37).

The cost of family violence includes lives lost, crisis response (police, ambulances, hospitals, courts, and frontline family violence and child protection services), healthcare, economic impact, property damage, lost work and disability. While updated economic modelling is set to be released shortly, it can be assumed that the current cost of family violence remains high.

The benefits of preventing violence

The avoidable personal, community and statewide costs of gendered violence, family violence and all forms of violence against women are significant. Decades of evidence from Victorian, Australian and international efforts shows that it is possible to successfully prevent violence if such efforts are concerted, coordinated and sustained across the social ecology (4).

Health and safety

Preventing violence reduces rates of trauma-related chronic illness and disability, including PTSD/C-PTSD, psychological distress (including depression and anxiety), pelvic pain, chronic pain, autoimmune disease, heart disease, addiction and brain injury (38-47).

It also eases pressure over time on frontline family violence services and avoids costs to already struggling health, emergency services, police, justice, child protection and housing services and systems seeking to address poverty, homelessness and mental illness (26).

The economy

In addition to saving and improving lives, preventing gendered violence has significant long-term benefits for the economy.

In 2025, the Victorian Government estimated that their investment of $82.8 million in family and sexual violence systems will save $120–130 million over 10 years in avoidable costs, and will produce up to $140 million through economic benefits over the same period (48).

Economic modelling by Deloitte estimates that shifting harmful gender norms (one of the goals of prevention work and a precursor to seeing rates of perpetration fall) will grow the national economy by $128 billion per annum on average (49). On a household level, the economic gains associated with more flexible gender norms would translate to an additional $12,200 per year for every household across Australia. Even early shifts in gender norms will improve labour market engagement and productivity (49).

Prevention is about transformational change and, as outlined in the Deloitte modelling, efforts require sustained investment to yield strong future economic returns. While Victoria has demonstrated commitment to addressing family violence and all forms of violence against women, investment needs to be sustained at higher than existing levels across the spectrum of primary prevention, early intervention, response, recovery and healing. Combined with leadership, policy reform, and collaboration this will create the safe and prosperous state that Victorians are seeking (50).

Victorian society

Primary prevention is about social change that will ultimately eradicate violence at the root causes. By doing so, it contributes to a healthier, fairer future where everyone can flourish. Addressing the drivers and reinforcing factors of gendered violence will remove the constraints that rigid gender stereotypes, gender inequality and harmful forms of masculinity place on people of all genders. It will support community safety, mental and physical health, economic participation and community inclusion.

Policy and social context

Over the reporting period there have been significant social, economic and political shifts that have impacted on the prevention landscape in Victoria.

Ongoing effects of the COVID-19 pandemic

Victoria has continued to feel the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic and its corresponding public health measures. As reported in Respect Victoria’s 2022 Report to Parliament on the Progress of Prevention, the pandemic ‘caused major disruptions to the prevention system and program implementation’. Primary prevention was made less of a priority as significant additional resources and attention was understandably focused on crisis response work and service delivery amidst a completely new and immensely challenging service delivery environment (2).

From 2022 onwards, with lockdowns over, the Victorian community attempted to adjust with increased economic debt and cost of living pressures, ongoing mental and physical health impacts, and an arguably more fractured and polarised society (51, 52). The impacts on young people and schools continued to be felt with widespread teacher shortages due – at least in part – to burnout and a reported rise in misogyny towards female teachers, a significant increase in school non-attendance and anxiety among students, and a cohort of children and young people whose formative social and emotional development (including through participating in the Respectful Relationships initiative in school and early years settings) had been significantly disrupted (51, 53, 54).

Backlash and resistance

These changed social conditions – together with rising influence of the ‘manosphere’ and misogynistic extremists radicalising young men through online platforms, the media and social commentary surrounding developments in global politics and high-profile family violence and sexual assault cases locally and internationally – have created fertile ground for intensifying backlash to gender equality, spurred by a quickly evolving technology landscape (55, 56). This influence has been compounded by the large amount of time Victorians, especially young people and children, have spent online since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, with other avenues for socialisation and education not available for long periods. Resistance and backlash to gender equality efforts have always been present and are an expected part of progressive social change; however, report participants highlighted the unique and complex ways that backlash has manifested and intensified over the past three years due to these factors (55, 56).

Report participants also highlighted the ongoing and intensifying anti-LGBTIQA+ backlash internationally and across Australia, which has caused, and continues to cause, profound harms to LGBTIQA+ communities, particularly trans and gender diverse people, who have been targeted through hateful social and political discourse and direct violence at a community level (57). Participants reflected on the intrinsic links between these forms of violence and discrimination and the crucial need to address them through the broader prevention effort.

There has been a marked increase in the development and uptake of generative AI tools and apps during the reporting period. Participants observed that such technology has been increasingly weaponised to perpetrate violence against women, including through the creation and distribution of non-consensual ‘deepfake’ pornography (58).

Significant backlash and resistance have also been targeted towards First Nations people during and following the federal referendum on a First Nations Voice to Parliament. Aboriginal leaders and organisations have since spoken about the impacts that the majority ‘No’ vote and divisive national debate and subsequent racist rhetoric had, and continues to have, on Aboriginal peoples’ physical, psychological and spiritual wellbeing, as well as on their trust and willingness to engage with mainstream services and organisations, and in Australia’s commitment to reconciliation, truth and justice (59).

Rates of violence

Between January 2022 and December 2024, 245 Australian women were killed or allegedly killed through acts of gendered violence, the majority by a current of former partner (60) (footnote 5). There were 98,816 police recorded incidents of family violence in 2023-24 – the highest number in five years, likely reflecting – at least in large part – increased community awareness of what behaviours constitute family violence and growing trust and willingness to report (62, 63). A number of deaths sparked considerable media reporting, community anguish and increased the national conversation about gendered violence. In Victoria, there was significant community mobilisation calling for a stop to violence against women (64).

Mobilising efforts have, in large part, been spurred by the powerful, ongoing advocacy of groups such as Counting Dead Women and Sherele Moody’s Australian Femicide Watch, and the media reporting on a number of deaths of women, including Samantha Murphy, Rebecca Young and Hannah McGuire in Ballarat in 2024, and far too many women since, allegedly at the hands of men, in tragedies that could have been avoided (60, 64).

This increased attention on the importance of addressing gendered violence, family violence and all forms of violence against women created a catalyst for renewed investment and commitment to strengthening primary prevention efforts and the need to continue to resource and support innovation, community-led initiatives and evidence-building.

The voices of Aboriginal leaders and ACCOs also culminated in the announcement of a federal inquiry into missing and murdered First Nations women and children released in 2024 (65, 66). Sadly this report did not receive the volume of media coverage it deserved, but it garnered an important commitment from the Australian Government in September 2024, to explicitly consider the needs and experiences of First Nations people, including in the release of the upcoming National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Family Safety Plan.

Overview of Victorian Policy Context 2022–24

Victorian Government family violence reform snapshot

The Victorian Government’s prevention efforts are informed by a range of strategies and governance frameworks intended to drive whole-of-government reform. This includes the following:

- Free from violence: Victoria’s strategy to prevent family violence and all forms of violence against women – Second rolling action plan 2022–2025 (2021) – this was the Victorian Government’s guiding policy document for primary prevention over the reporting period. Ongoing implementation has been consolidated into Until every Victorian is safe: Third rolling action plan to end family and sexual violence 2025 to 2027, released in September 2025 outside of the reporting period (5, 67, 68).

- Ending family violence: Victoria’s plan for change (2016) – this is the overarching 10-year strategy guiding Victoria’s family violence reforms (from prevention through to response), which has been implemented through a series of rolling action plans. The current rolling action plan ended in 2023, and the next one was published outside the reporting timeframe in 2025 (69).

- Building from strength: 10-Year Industry Plan for Family Violence Prevention and Response (2017) – this industry plan outlines the long-term vision for the workforces that prevent and respond to family violence (70).

- Dhelk Dja: Safe Our Way – Strong Culture, Strong Peoples, Strong Families (2018) – this strategy was developed in partnership with Aboriginal communities across Victoria to guide self-determined, Aboriginal-led family violence prevention and response. Implementation is achieved through a series of three-year action plans (71).

- Everybody matters: Inclusion and equity statement (2018) – this statement was operationalised through an inaugural three-year blueprint (2019–2022). Ongoing implementation has been consolidated into the Ending Family Violence rolling action plan (72).

- Our equal state: Victoria’s gender equality strategy and action plan 2023–2027 (2023) – this is Victoria’s roadmap for action on gender equality (73).

- Roadmap for Reform: Strong families, safe children (2016) – this is Victoria’s strategy focusing on reform of the Victorian children, youth and families system, shifting the focus from crisis response to prevention and early intervention (74).

Oversight and implementation of these various strategies are guided by a series of governance structures intended to drive whole-of-government reform. These include the Family Violence Reform Advisory Group, Victim Survivors’ Advisory Council, Dhelk Dja Partnership Forum and Primary Prevention Sector Reference Group.

Royal Commission into Family Violence recommendations acquittal

On 28 January 2023, the Victorian Government announced the acquittal of the 227 recommendations from the 2015 Royal Commission into Family Violence. With this, the mandate for the Family Violence Reform Implementation Monitor, set up to oversee and monitor progress of the recommendations’ implementation, was fulfilled, and this important accountability structure was ended.

Of course, implementation of the royal commission recommendations did not mean the problem of family violence and violence against women was solved. Recognising this, the Victorian Government released Strong Foundations, which set the direction for the next stage of family violence reform in Victoria and signalled the Victorian Government’s commitment to the ongoing, unfinished work of preventing and addressing family violence and violence against women. As then Minister for Prevention of Family Violence, Vicki Ward MP stated:

Our goal is to end this violence. This requires unwavering work towards generational change. We cannot step back from this challenge. It is our unfinished business (75).

See Enabling policy and legislation for a discussion of key progress and developments during the reporting period.

Free From Violence Strategy

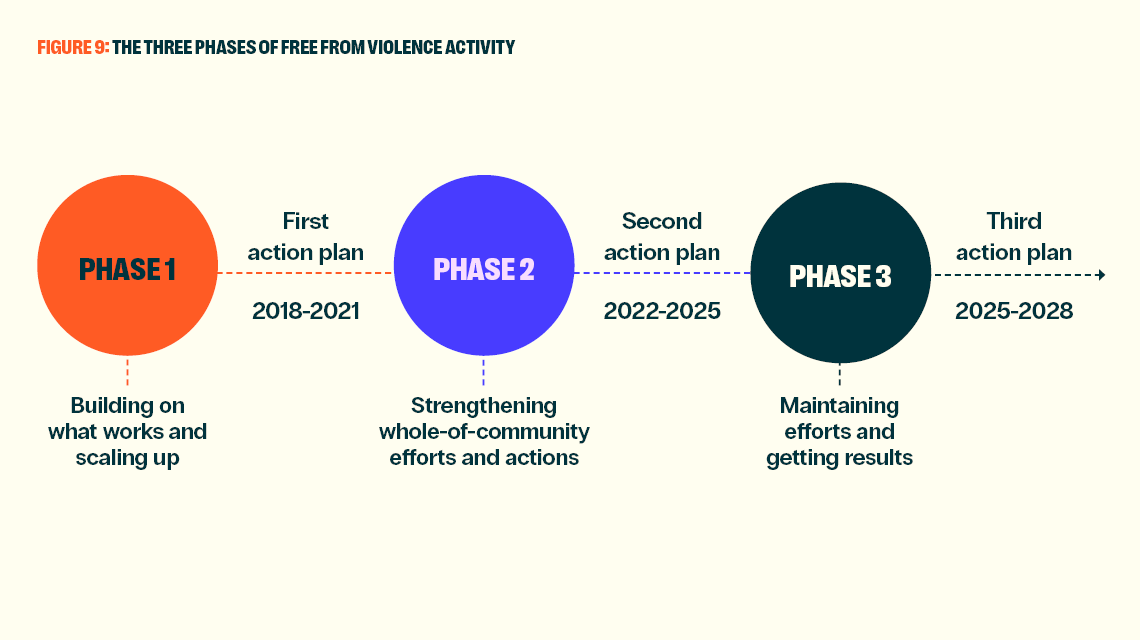

Free from violence: Second action plan 2022-2025, co-designed and delivered by Family Safety Victoria and Respect Victoria, was the guiding policy document for primary prevention in Victoria during the reporting period. As the second phase of delivering the 10-year Free from Violence Strategy, its focus was on ‘strengthening whole-of-community efforts and actions’. It included 10priority areas:

- testing new and innovative approaches

- tailored approaches for diverse community groups

- Aboriginal-led prevention

- key settings

- community engagement and awareness

- partnerships and advocacy

- governance, coordination and system development

- workforce and sector development

- build knowledge

- monitor and share outcomes.

Almost all actions aligned with these priority areas were acquitted over the reporting. Specific progress and achievements are outlined in Prevention investment and Enabling Policy and Legislation. Importantly, this crucial work was intended to lead into the final, forthcoming phase of the Free from Violence strategy. The pathway of intended change can be seen in the diagram below (footnote 6).

Yoorrook Justice Commission

The work of the Yoorrook Justice Commission has also influenced the political and social context of prevention in Victoria, especially the support required for Aboriginal-led prevention. Three of the 100 recommendations made by the commission relate specifically to family violence. These are:

- the establishment of a Victorian First Peoples’ prevention of family violence peak body

- sustainable, long-term funding to ACCOs to expand and deliver new initiatives to respond to family violence, including centres for First Peoples women affected by family violence

- investment in primary prevention initiatives that also address racism.

The Yoorrook Justice Commission was established in May 2021, becoming Australia’s first formal truth-telling process into historical and ongoing injustices experienced by First Peoples in Victoria. The commission held six blocks of public hearings within the reporting period, with a focus on injustices against First Peoples in the child protection and criminal justice systems, including a thematic focus on family violence, as well as public hearings about land, sky and waters, and health, housing, education and economic justice. The commission delivered three interim reports and made 146 recommendations for reform – three of which related to family violence, as noted earlier. The commission’s final report was tabled in Parliament on 1 July 2025.

Changing the picture and the work of Dhelk Dja highlight the legacy of colonisation and ongoing systemic racism as key drivers of the unacceptably high rates of violence against Aboriginal women. The work of the Yoorrook Justice Commission has highlighted how redressing the wrongs of the past, supporting First Peoples’ self-determination and Aboriginal-led prevention efforts are – and must continue to be – central to Victoria’s efforts to prevent family violence and all forms of violence against women (24).

Overview of federal policy context 2022–24

Australian Government family violence reform snapshot

- The National Plan to End Violence against Women and Children 2022–2032 – released in October 2022 – it outlines a vision to end gendered violence in one generation. While focused on violence against women, children are recognised as experiencing violence in their own right, and updated terminology includes gendered violence against LGBTIQA+ people (76).

- Working for Women: A strategy for gender equality – released in March 2024, it prioritises the prevention of gendered violence through addressing both gendered drivers and risk factors such as financial inequality and insecurity, unpaid caring roles, and health and disability (77).

- The Action Plan Addressing Gender-based Violence in Higher Education – released in February 2024 – it aims to create higher education communities free from gendered violence (78).

- The National Strategy to Prevent and Respond to Child Sexual Abuse 2021–2030 – it is a nationally coordinated, strategic framework for preventing and responding to child sexual abuse (79).

- Safe and Supported: The National Framework for Protecting Australia’s Children 2021–2031 – it is a framework for governments, community organisations and First Nations leaders to reduce the rate of child abuse and neglect and its impacts across generations (80).

- Australia’s Disability Strategy 2021–2031 – it outlines a vision for a more inclusive and accessible Australian society where all people with disability can fulfil their potential as equal members of the community (81).

- The National Women’s Health Strategy 2020–2030 – it is Australia’s national approach to improving the health of women and girls – particularly those at greatest risk of poor health – and to reducing inequities between different groups (82).

- The National Health and Climate Strategy – released in December 2023 – it outlines an intersectional, cross-portfolio approach to supporting healthy, climate-resilient communities, including recognition of the disproportionate impacts of climate disaster on women and girls (83).

- The National Plan to Respond to the Abuse of Older Australians (Elder Abuse) 2019–2023 – it sets out the Australia’s cross-government framework for preventing and responding to the abuse of older people (84).

Throughout the reporting period, there have been several federal policy and legislative developments at the national level with implications for prevention work in Victoria. These include:

- the establishment of the Domestic, Family and Sexual Violence Commission

- the ongoing work and national leadership of Our Watch

- the Rapid Review of evidence-based approaches to prevent gender-based violence (discussed further below)

- the first standalone Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Action Plan (2023–2025) under the National Plan to Prevent Violence Against Women and Children

- the continuation of funding through the Family, Domestic and Sexual Violence Responses 2021–30 schedule under the Federation Funding Agreement – Affordable Housing, Community Services and Other and the Family, Domestic and Sexual Violence National Partnership Agreement

- the inquiry into missing and murdered First Nations women and children

- the Royal Commission into Violence, Abuse, Neglect and Exploitation of People with Disability

- the Online Safety Act 2021 (Cth) coming into force in January 2022, giving the eSafety Commissioner substantial new powers to protect adults and children from harm across most online platforms and forums where people can experience harm (85)

- the enacting of federal reforms to the Sex Discrimination Act 1984 (Cth), which made it clear that it is unlawful to subject another person to a workplace environment that is hostile on the grounds of sex (86)

- National Cabinet commitments including strengthening accountability of high-risk perpetrators and focusing on efforts to prevent impacts of violent pornography and online misogyny (87)

- national higher education reforms to address gendered violence including an action plan, National Student Ombudsman and National Higher Education Code to Prevent and Respond to Gender-based Violence (78).

Over the reporting period, the Australian Government has continued to progress the development of several prevention-related frameworks and strategies. This includes adapting the National Plan to Prevent Violence Against Women and Children for disability-specific contexts, consultation on the development of the National Plan to End the Abuse and Mistreatment of Older People 2025–2035, and consultation on the forthcoming National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Family Safety Plan (88, 89).

Rapid review of evidence-based approaches to prevent gender-based violence

In conjunction with the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet, the Domestic, Family and Sexual Violence Commissioner co-convened an expert panel to undertake a rapid review of evidence-based approaches to prevent gender-based violence. The final report from the Rapid Review of Prevention Approaches was delivered on 23 August 2024 (90). It made recommendations across six areas, including that Commonwealth and state and territory governments to agree that 'ending gender-based violence, including violence against children and young people' becomes an ongoing priority of National Cabinet.

Other recommendations included:

- establishing a co-funded Prevention Innovation Fund

- undertaking an independent review of Change the story

- prioritising the needs and experiences of First Nations people

- focusing on children and young people, men and masculinities, and strengthening women’s economic inequality

- embedding prevention through response services, systems and industries.

While report participants had diverse views about the rapid review’s process and a number of its recommendations, many felt it brought renewed attention to the strengths of Victoria’s current prevention efforts and underscored the importance of addressing all determinants of violence outlined in Change the story – gendered drivers, reinforcing factors and overlapping forms of oppression and inequality – as well as distinct drivers of specific types of gendered, family and sexual violence, and their impacts on particular cohorts. It also highlighted opportunities to leverage cross-sector, government and industry ownership and collaboration to target commercial or market-based contributors to violence – such as pornography, alcohol, gambling and the incentivisation of harmful content across digital platforms and settings.

Footnotes

These are the most updated Personal Safety Survey data available within the reporting period.

This diagram includes organisations with responsibilities for prevention oversight or delivery or otherwise brought to our attention through this review. It does not capture all organisations with a role in primary prevention, nor does it capture governance arrangements and partnerships.

These include the Working with Women Alliance, National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Women's Alliance, National Rural Women's Coalition, Women with Disabilities Australia, and Australian Multicultural Women's Alliance. Further information can be found at: www.pmc.gov.au/office-women/working-for-women-program/national-womens-alliances.

The Family Violence Reform Implementation Monitor delivered its final report in January 2023. It subsequently ceased operations in line with the Victorian Government announcing on 28 January 2023 that it had acquitted all 227 recommendations from the Royal Commission into Family Violence.

It is worth noting that these figures do not include deaths by suicide related to family violence or gendered violence. A recent Coronial finding noted that the link between family violence and suicide is under-researched and that increased resourcing for the Coroners Court of Victoria would yield better quality data and analysis of this relationship (61).

The next stage of this work has been consolidated into Until every Victorian is safe: Third rolling action plan to end family and sexual violence 2025 to 2027, which was released in September 2025, after the reporting period.