On this page

This section aligns with the following domain of the Theory of Change:

- 1.1 Government legislation, regulation, policy

Legislative reforms and policy implementation are integral to prevention work. They provide the enabling environment for prevention activity and play an important transformative role in systems and social change.

Where progress has been made

The Royal Commission into Family Violence was a catalyst for significant legislative and policy reform in Victoria. Importantly, this included the development of Free from Violence – Victoria’s current 10-year strategy to prevent family violence (5). This strategy – together with the overarching Ending Family Violence plan, Safe and Strong gender equality strategy and Dhelk Dja: Safe Our Way strategy – set the agenda for long-term change.

Report participants acknowledged that strong legislative reform and strategic policy implementation have been instrumental in creating the enabling environment for effective prevention work in Victoria during the reporting period. More than half (59%) of the participants surveyed for this report believed that the policy and legislative environment has improved in support of preventing gendered violence, compared to three years ago, with a further 27% indicating they believed the enabling environment had remained the same.

Free from Violence Second Action Plan

The Victorian Government released Free from violence: Second action plan 2022–2025 under the 10-year strategy to prevent violence and all forms of violence against women (67). As previously noted, this was the guiding policy document for primary prevention in Victoria during the reporting period and, at the time of its launch, it was nation-leading in having a singular focus on primary prevention supported by wide-ranging actions across key settings and life stages backed by dedicated investment. It was co-designed and delivered by Family Safety Victoria and Respect Victoria. The plan comprises 10 priorities across five pillars: innovate and inform; scale up and build on what we know works; engage and communicate with the community; build prevention systems and structures; and research and evaluate. At the time of writing, almost all actions under the plan had been successfully acquitted, with the final remaining actions on track for delivery as part of the newly released Until every Victorian is safe: Third rolling action plan to end family and sexual violence 2025 to 2027. Key impacts and achievements included engaging Victorians in preventing family violence through over 250 initiatives in the places where they live, work, learn and play, and running over 332,000 sessions of MARAM or MARAM-aligned training with workers.

Ending Family Violence third rolling action plan

The outstanding actions from the Free from Violence Second Action Plan (2022–2025) and priorities outlined in Strong Foundations were operationalised through the next rolling action plan under Victoria’s Ending Family Violence strategy – initially due for delivery in 2023 and ultimately released outside of the reporting period in September 2025. The Victorian Government has consolidated several family violence-related action plans into the new Until every Victorian is safe: Third rolling action plan to end family and sexual violence 2025 to 2027, so will no longer have a standalone plan for primary prevention. This consolidation has the potential to support greater integration and connection of primary prevention with the broader family violence system and provide a cohesive strategy across the family violence reforms. Notably, however, this consolidation runs counter to the advice of Our Watch that all states and territories in Australia should enact dedicated primary prevention strategies. In the years ahead, it will be crucial to ensure that the consolidated approach does not result in a dilution of action or investment in primary prevention.

Affirmative consent legislative reform

The Victorian Government introduced a range of reforms through the Justice Legislation Amendment (Sexual Offences and Other Matters) Act 2022 (Vic), which came into effect on 30 July 2023. These reforms included adopting an affirmative consent model, putting the responsibility on each person involved in a sexual activity to seek explicit consent (121).

The reforms also introduced stealthing (the removal, non-use or tampering with a condom without the other person’s knowledge or consent) as a sexual offence, stronger laws that target image-based sexual abuse – including an expanded definition of ‘intimate image’ and a higher maximum penalty – as well as new jury directions to address misconceptions in sexual offence trials.

Gender Equality Act

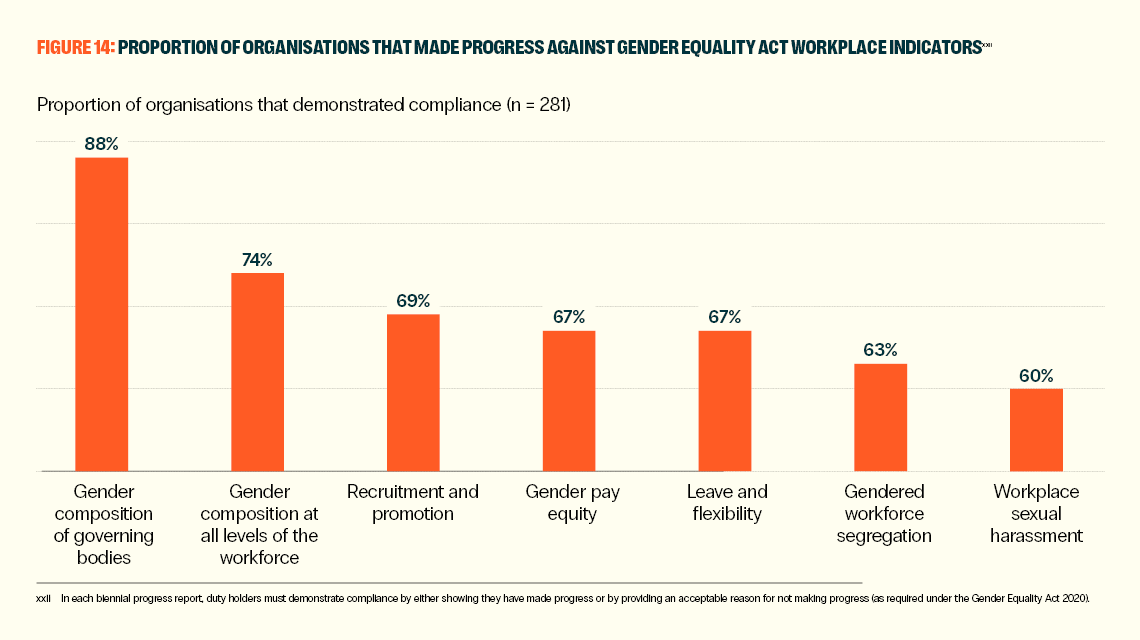

The Gender Equality Act 2020 (Vic) and the role of the independent Public Sector Gender Equality Commissioner were only just established at the time of the inaugural Three Yearly Report to Parliament. Considerable progress has been made with the implementation of the Act over this reporting period, with approximately 300 duty holders meeting their obligations to do a gender audit and submit gender equality action plans and progress reports (122). The Commission for Gender Equality in the Public Sector and other stakeholders, including the Municipal Association of Victoria and some women’s health services, played important roles supporting duty holders to understand and respond to their obligations under the Act, including by dedicating considerable resources to capacity building and establishing regional communities of practice and partnerships (123).

Figure 14: Proportion of organisations that made progress against the workplace gender equality indicators, according to the Commission for Gender Equality in the Public Service (footnote 1) Source (123)

Other important developments

The Ministerial Taskforce on Workplace Sexual Harassment handed down its recommendations in 2021. This included an overarching recommendation that workplace sexual harassment be treated as an occupational health and safety issue and for WorkSafe to play a lead role in the prevention of, and response to, workplace sexual harassment. WorkSafe Victoria and the Victorian Equal Opportunity and Human Rights Commission are now partnering to regulate work-related gendered violence, including sexual harassment through their Parallel Enforcement Strategy (125).

The Office for Women in Sport and Recreation, in partnership with VicHealth and Sport and Recreation Victoria, released the Fair Access Policy Roadmap, which aims to ensure women and girls across the state have equal access to community sports facilities – settings that are critical to preventing gendered violence, particularly violence against women (126). The roadmap requires that all local governments across Victoria develop a Fair Access Policy and demonstrate their progress against these policies over time, building on their existing obligations under the Gender Equality Act 2020 (Vic) (124) (footnote 2).

The Victorian Government released Our equal state: Victoria’s gender equality strategy and action plan 2023–2027, committing to 110 actions over four years to advance gender equality, many of which address the gendered drivers of violence and complement the priorities and activity outlined in Free from Violence (73). Key legislative achievements within the first year of its implementation included reforms to introduce affirmative sexual consent in the Justice Legislation Amendment (Sexual Offences and Other Matters) Act 2022 (Vic) and non-fatal strangulation offences.

Other relevant developments over the reporting period include:

- implementation of the regulatory framework for Child Safe Standards in schools to supporting implementation of the Respectful Relationships initiative (127)

- expanded rollout of the Family Violence Multi-Agency Risk Assessment and Management (MARAM) Framework, including in schools (128)

- development of the Social Procurement Framework to support the Victorian Government to better identify and support women-led and diverse business (129)

- start of a process to refresh the 2012 Indigenous Family Violence Primary Prevention Framework (due for release in 2025) (130)

- consultation on proposed reforms to Victoria’s anti-vilification laws expanding existing protections against hate speech and conduct on the basis of race and religion to include gender identity, sex, sex characteristics, sexual orientation and disability (131, 132) (footnote 3)

- a Victorian parliamentary inquiry into capturing data on people who use family violence in Victoria

- release of Ageing well in Victoria: An action plan for strengthening wellbeing for senior Victorians 2022–2026, which outlines the Victorian Government’s commitment to support Victorians to age well by continuing to participate in their community, and be safe at home, in the community or aged care (133)

- consultation in 2023 on the Australian Law Reform Commission’s inquiry into justice responses to sexual violence, which prompted important recommendations on harnessing the justice system as a setting for prevention in recognition of the normative role that laws, legal proceedings and legal professionals play in shaping and reinforcing social norms related to sexual violence (134)

- consultation in 2024 for the Inquiry into Women’s Pain, the final report of which, expected for release in 2025, will address medical gender bias through providing recommendations to inform improved models of care and service delivery for Victorian girls and women experiencing pain (135).

Where there are challenges?

Report participants noted that family violence reforms to date have largely focused on intimate partner violence within family contexts, and that the use of family violence as the dominant policy framing and language both minimises the gendered nature of family violence and reinforces rigid ideas about what family relationships look like and the types of violence experienced within them. They also noted that this policy framing has rendered other forms of gendered violence largely invisible, particularly non-partner violence and sexual violence (by a partner or non-partner).

If we just frame it as family violence, actually there’s all this other violence that people are experiencing, and if that’s out of the agenda, we’re undermining our efforts. – Kathleen Maltzahn, Sexual Assault Services Victoria

Similarly, report participants highlighted the more limited policy focus to date on preventing other forms of family violence and gendered violence – including violence against children and young people, adolescent violence in the home, and elder abuse – as well as the ways that violence experienced by LGBTIQA+ people can be obscured by policy responses that are consciously or unconsciously built upon heterosexual and cisgender models. Participants highlighted the need to broaden the policy framing and agenda for family and gendered violence to better reflect the scope and nature of the issues, and to ensure policy priorities, funding, evidence and practice are developed accordingly.

Focus on sexual violence slipping through the cracks

Sexual violence was seen as a major policy gap by several report participants, with some suggesting the need for a standalone Victorian sexual violence prevention strategy and an explicit commitment to preventing and addressing sexual violence in policies and strategies that tackle family violence and all forms of violence against women (footnote 4). Participants discussed the importance of targeted prevention of sexual violence not just in intimate partner relationships, but also non-partner sexual assault, child sexual abuse and the sexual exploitation of adolescents both online and in real-world settings. Establishing a strong policy foundation for sexual violence prevention is needed to guide adequate investment, the development of evidence and practice frameworks and support the development of the workforce.

The coverage and representation of sexual violence and gender-based violence that [doesn’t occur] in a family violence setting. I think that’s one of the biggest policy risks in Victoria that people have been grappling with since the royal commission; family violence is the major framing and other forms of violence are missed and untold and invisible in that. – Prevention organisation executive

I think a big missing focus is sexual-based violence … we don’t get anywhere near the significant amount of prevention work that we need to do without this as a key pillar and focus. – Anonymous report participant

In recognition of this issue, the Victorian Government has moved to using the language of ‘family and sexual violence’. This is a welcome signal that invites explicit consideration of the additional, distinct and complex drivers of sexual violence. Ensuring that this framing translates into meaningful action will need to be an ongoing focus, including by actively addressing the gendered nature and nuances of both family and sexual violence within and outside of heteronormative and cisnormative relationships.

Respect Victoria’s analysis of the NCAS data reveals that harmful attitudes towards sexual violence remain challenging to shift and this must be an ongoing priority within prevention efforts. Although the majority of Victorians and Australians reject sexual violence, Victorian men demonstrate higher agreement with attitudes that minimise, deny or shift blame in cases of sexual violence than Victorian women (136). In addition, attitudes towards sexual violence appear to be an area of increasing polarisation and backlash against gender equality and prevention efforts, indicating a need for more targeted action and concerted focus in Victorian policy and legislation.

Report participants also highlighted the role of violent pornography and the increasing normalisation of non-fatal strangulation during sexual activity as concerning trends that lead to harm and are not yet being given the policy and legislative attention required to reduce such harm.

Children and young people need more tailored approaches

Report participants highlighted the need for prevention policy that truly includes the voices and experiences of children and young people. Children and young people may experience family and gendered violence within their families and intimate relationships, and some use gendered violence themselves. However current policy framing often positions them as passive recipients of violence experienced by their mother. This misses the opportunity to drive targeted prevention of the unique and complex forms of violence that far too many children and young people experience by virtue of their age and corresponding vulnerability (e.g. child maltreatment, adolescent violence in the home, and gendered violence within emergent intimate partner relationships).

I think there’s a lot more work that needs to be done to have a dedicated focus on primary prevention initiatives that work well with and for children and young people, and to actually not think of children and young people as the recipients of a product. It should be an intended consequence of these initiatives to elicit disclosures from victim-survivors. – Family violence youth advocate

Children and young people should be viewed as more than agents of change for preventing future adult violence. Report participants highlighted that more needs to be done to tailor programs and activities that target particular forms of violence impacting children and young people and, in particular, to support children and young people at risk of experiencing violence, or showing early signs of harmful beliefs and behaviours.

I received [Respectful Relationships] education in the later years of my schooling … I didn’t see myself or hear myself represented in the way they were talking about family violence [at school]. It was focused on violence against women, to be frank, and missed out on other intersecting forms of violence. But still, the things and the topics and the warning signs that they were talking about, I was like, well, I’ve experienced that … I guess that’s when I realised that primary prevention has the ability to be a mechanism to intervene and prevent family violence from continuing to occur. – Family violence youth advocate

In Strong Foundations, the Victorian Government committed to prioritise engaging children and young people to create generational change and continuing to tailor prevention and early intervention projects that work with children and young people at heightened risk of experiencing or using family or sexual violence (75). Actioning this commitment should now be a key priority.

Early intervention is a missing piece

Report participants highlighted the limited focus on early intervention in current Victorian policies and strategies, particularly how it integrates with primary prevention efforts. Primary prevention and early intervention work together by unwinding the harmful attitudes held by people who use violence and helping them to take responsibility for their choices and learn new behaviours. The Victorian Government and Australian Government have recently invested in early intervention initiatives, and response agencies are making important contributions, but a more coherent and strategic approach is needed to guide future priorities, actions and practice in this area (138, 139). This will allow prevention activities and the workforce to better support those at risk of experiencing and perpetrating violence, alongside delivering crucial whole-of-population initiatives.

There’s a lack of early intervention and by early intervention, I mean early-early intervention. We’re talking about children in primary school who have harmful beliefs and behaviours, but they have not broken any law or even broken a school rule, but there’s a pattern of behaviour, there’s a lack of support for those children, and I think that’s a huge impediment. – Deanne Carson, Body Safety Australia

Opportunities for action

Stronger policy coordination

Report participants raised the importance of stronger policy coordination across portfolios and departments. This includes between Victorian, federal and local governments, noting their respective legislative and regulatory roles, commitments under the National Partnership Agreement on Family, Domestic and Sexual Violence Responses, and shared priorities under the National Plan to End Violence against Women and Children.

The national Domestic, Family and Sexual Violence Commission – together with Our Watch – create a strong coordinating opportunity to pull together areas of work across the nation and support connection with federal policy, programming and evidence building.

There are also opportunities, particularly through the national Domestic, Family and Sexual Violence Commission and Our Watch, for jurisdictions across Australia (including Victoria) to continue to share successful policy and strategy initiatives, with a view to harmonising and tailoring approaches where appropriate, learning about best and emerging practice, and tailoring where needed. For example, actions under the National Plan to End Violence against Women and Children – such as developing, implementing and evaluating prevention tailored to specific communities – have seen greater progress in some states or territories. This is a good opportunity for Victoria to both share what it has learnt and adopt successful work already trialled elsewhere. While the National Commission has sought to enable such conversations through convening national consultations and roundtables, it is unclear how they are being translated into decision making in formal intergovernmental structures. Ongoing collaboration between the National Commission and Respect Victoria could support national coordination and propel Victoria and Australia’s progress forwards.

Address emerging technology-facilitated harms

To remain effective and responsive, Victoria’s prevention system must address emerging and escalating forms of gendered harm. The digital sphere presents a rapidly evolving landscape where violence and abuse – including technology- and AI-facilitated abuse, the proliferation of violent pornography, and prominence of misogynistic extremists – are increasingly normalised and difficult to regulate. Developing coordinated strategies in partnership with local, state, territory and federal governments, and public entities (particularly eSafety) is not just an important opportunity, but essential to preventing harm, protecting the right to engage safely with online spaces and technology, and ensuring that policy and regulatory responses keep pace with technological change. In Strong Foundations, the Victorian Government explicitly acknowledged and committed to address these issues. Actioning this commitment should now be a key priority (75).

Prioritise, collaborate and coordinate early intervention

Victoria’s introduction of MARAM has been a key innovation and enabler of early intervention. Yet, the work of early intervention itself has received more limited emphasis in Victorian family violence policy, despite being a crucial component of a comprehensive approach to ending family violence, gendered violence and all forms of violence against women (140). Introducing a greater focus on early intervention would allow policymakers to identify gaps and opportunities in Victoria’s approach and strengthen collaboration and coordination across the prevention and response systems and across government for greater impact.

Primary prevention and early intervention are distinct but complementary approaches: working together, they reduce the prevalence, severity and recurrence of violence over time. While early intervention work is being progressed across the state – supported by a range of government departments, specialist family violence services and child, youth and family services – no one team has oversight of the entire system, nor is there an agreed or sophisticated understanding of the early intervention landscape in Victoria. Without this, key policy gaps and opportunities will remain obscured.

For example, much of the existing early intervention work in relation to family and sexual violence takes place within specialist family and sexual violence services, and there is an opportunity to coordinate efforts to enable mutual reinforcement of such efforts with primary prevention work for greater impact (140). This approach is envisaged for Respect Ballarat (see case study). This is also particularly important to the prevention of family violence in First Nations communities, where there is greater harmony across primary prevention and early intervention settings and efforts. Like many specialist family and sexual violence services, they aim to strengthen protective factors, support early identification of risk factors and ensure people at risk of experiencing or using violence receive support as early as possible to change the trajectory of violence.

Increased policy attention on early intervention will also support strengthened efforts to prevent violence against children and young people. For example, it is important to highlight and connect initiatives such as adolescent family violence programs, responses to harmful sexual behaviour in children and young people and Caring Dads programs – these are critical to intervene early and change behaviour, and interrupt the intergenerational effects and the longer-term trajectory of violence.

Recommendations

Respect Victoria recommends that the Victorian Government:

- Develop and implement a statewide strategy for preventing and addressing sexual violence, or at least ensure there is dedicated focus, action and investment on preventing sexual violence throughout implementation of the Until every Victorian is safe: Third rolling action plan to end family and sexual violence 2025 to 2027 and other relevant strategies.

- Work with and advocate to the federal government and other jurisdictions for effective strategies to safeguard against new and/or escalating gendered harms in the digital space.

- Work in partnership with the prevention and response sector to agree on an approach for statewide monitoring and coordination of early intervention approaches across government departments and agencies, and the Victorian community.

Footnotes

In each biennial progress report, duty holders must demonstrate compliance by either showing they have made progress or by providing an acceptable reason for not making progress (as required under the Gender Equality Act 2020). Source: (123).

The Office for Women in Sport and Recreation came to a close in September 2025. Implications for monitoring these obligations are therefore unclear going forward.

A bill was subsequently introduced, passed and received royal assent in April 2025, outside of the reporting period.

The Victorian Government previously committed to deliver a sexual violence and harm Strategy in 2022. See Victorian Government press release, Stronger laws for victim-survivors of sexual violence, 12 November 2021.